English author Patsy Trench with early Hawkesbury ancestors has researched in depth the state of the Hawkesbury in its earliest days. Here she reveals the Hawkesbury’s connection with the Rum Rebellion in Sydney.

Create a free account to read this article

$0/

(min cost $0)

or signup to continue reading

I first came upon the Rum Rebellion in the course of researching a book I was writing about my Australian ancestors the Pitt family, who were early Hawkesbury settlers.

I learned that on 26 January 1808, 20 years to the day since the arrival of the First Fleet, 300 soldiers from the NSW Corps, led by Major George Johnston, marched with full colours and military band playing ‘The British Grenadiers’ up Bridge Street in Sydney.

Their destination was Government House, to arrest Governor Bligh. The only person who tried to stop them was Bligh’s daughter Mary, armed with an umbrella.

The cause of the coup was the fact that the governor, who had been expressly appointed to curtail the growing power of the Corps, had managed to alienate virtually everyone in the colony except the Hawkesbury settlers in just two years.

To the people in the Hawkesbury district Governor Bligh had been an ally since his arrival in August 1806. He’d begun by granting them generous compensation for their terrible losses from floods. The friendship was strengthened by their mutual hatred of the NSW Corps. In an early letter of welcome in August 1808 representatives of Hawkesbury farmers, who included my three times great grandfather, wrote to Bligh hoping he would help break down the monopolgy and extortion practised by the NSW Corps.

On January 1, 1808, only weeks before the Rum Rebellion coup, they wrote to Bligh to “express the fullest and unfeigned sense of gratitude for the manifold, great, and essential blessings and benefits we freely continue to enjoy from your Excellency’s arduous, just, determined and salutary government over us”, promising their fervent support for him. The letter was signed by over 800 people, including my ancestor Thomas Matcham Pitt, who’d arrived in the Hawkesbury in 1802.

Then less than a month later and three days after the coup, another paper was circulated among the Hawkesbury inhabitants, this time condemning Governor Bligh and thanking his deposers. The letter stated that the only reason they had signed the letter was fear of reprisal.

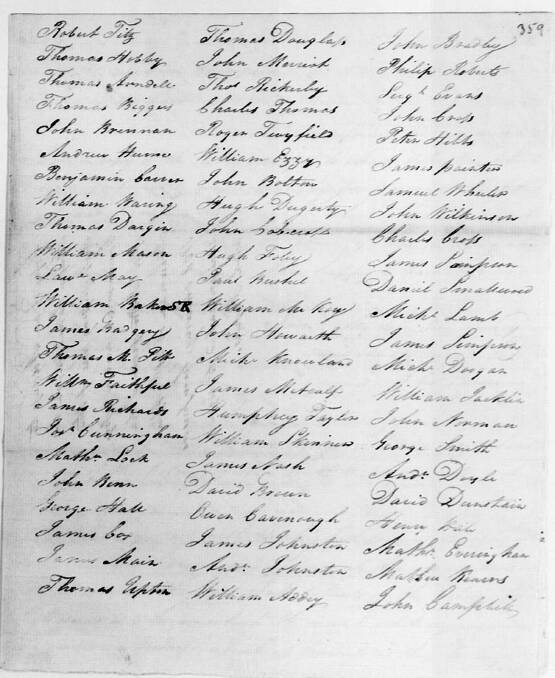

“Now that we can freely express the sentiments of our minds, we gladly beg to assure you that we are ready to support you with our lives and properties, conscious that every act of your administration would meet His Majesty’s approbation. We cannot in language sufficiently praise the meritorious services of the New South Wales Corps on this memorable occasion,” the new document said. This document was signed by more than 60 people, including Thomas Pitt.

Why had my ancestor signed a letter in support of Bligh and, less than a month later, another in support of his deposers? Moreover he wasn’t the only one. The surgeon and magistrate Thomas Arndell – a much respected member of the Hawkesbury community, who’d arrived with the First Fleet - was also a co-signatory of both missives. Were these otherwise honourable gentlemen turncoats, or cowards?

Two months later Arndell wrote to Bligh’s secretary Edmund Griffin confessing he had signed the letter “through fear, and without so much as knowing the contents at the time I signed it”.

Shortly after that a man named John Brennan wrote to Andrew Thompson, the high constable, to confess, “Mr Arndell informed me you wished to have a copy of the letter addressed to Major Johnston, which I was unfortunately concerned in, by going amongst the settlers to get their signatures thereto, and to which I sincerely repent in my duplicity in taking the advice of others ...”.

During the subsequent court martial of Major Johnston in England, a Hawkesbury witness said that on the night of the coup and several nights after there was a “general state of intoxication, riot, and confusion at Green Hills [Windsor]” and they burnt an effigy of the governor. He said at the end of January a number of Hawkesbury locals, some of whom were ex-NSW Corps, “drew up an address to Major Johnston sanctioning what had been done” and when fuelled up with alcohol had gone out to solicit signatures, with threats of gaol if they didn’t.